Fact Check: Are Painful Periods a Sign of Good Fertility?

Are painful periods a sign of good fertility? Learn the truth about dysmenorrhea, endometriosis, PCOS, and the vaginal microbiome in reproductive health.

Words by Olivia Cassano

Scientifically edited by Dr. Krystal Thomas-White, PhD

Medically reviewed by Dr. Kate McLean MD, MPH, FACOG

Thanks to the gender health gap, many people have grown up hearing that painful periods are “normal.” Menstrual cramps are so common that they’ve often been brushed off as a rite of passage, even framed as a marker of womanhood or proof that your body is working as it should. In fact, while some discomfort is normal, periods shouldn’t be painful. And rather than being a sign of strong fertility, painful periods can sometimes point to the opposite, especially when linked to conditions like endometriosis or adenomyosis.

Hormonal changes, reproductive health conditions, and potentially even imbalances in your vaginal microbiome can cause painful periods (known medically as dysmenorrhea). Understanding where the pain comes from can help you separate myth from fact when it comes to fertility.

What causes painful periods?

Painful periods, or dysmenorrhea, affect a large percentage of people who menstruate. For some, the discomfort is mild and manageable. For others, period pain can be so intense that it interferes with daily life, school, or work.

Menstrual cramps are caused by uterine contractions. When you’re on your period, the uterus produces hormone-like substances called prostaglandins. These chemicals trigger muscle contractions that help shed the uterine lining. The higher your prostaglandin levels, the stronger (and more painful) those contractions can be.

That said, not all period pain is the same. Doctors typically classify dysmenorrhea into two main categories: primary and secondary. Primary dysmenorrhea usually begins in adolescence, while secondary dysmenorrhea develops later in life and is often tied to underlying health issues (many of which could affect fertility). Understanding the difference is important when it comes to fertility and overall reproductive health.

Primary dysmenorrhea

Primary dysmenorrhea refers to menstrual pain without any underlying disease or pelvic condition. It usually starts in adolescence, within a few years after the onset of menstruation. The pain typically appears just before or during menstruation and can last for one to three days.

The main driver here is prostaglandins. Higher levels of these chemicals can lead to stronger uterine contractions, reduced blood flow, and cramping. While uncomfortable, primary dysmenorrhea is considered “functional” pain — it’s not linked to structural abnormalities or disease. Importantly, primary dysmenorrhea doesn’t mean reduced fertility. Many people with this type of period pain conceive without difficulty.

Secondary dysmenorrhea

Secondary dysmenorrhea is menstrual pain caused by an underlying reproductive health condition. This type of pain often starts later in life and may worsen over time. The most common causes include:

- Endometriosis: A common condition where tissue similar to the uterine lining grows on other organs outside the uterus, such as in the ovaries and fallopian tubes. Endometriosis is strongly associated with both severe menstrual pain and infertility.

- Adenomyosis: A disorder where uterine lining tissue grows into the muscular wall of the uterus, leading to heavy bleeding and painful cramps.

- Uterine fibroids: These can distort the uterus and contribute to painful menstrual cycles.

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): While not always associated with painful cramps in the same way as endometriosis or adenomyosis, PCOS can lead to irregular, heavy, or prolonged menstrual bleeding. For some people, these cycle disruptions and hormonal imbalances may contribute to pain and discomfort.

Unlike primary dysmenorrhea, secondary dysmenorrhea often signals a chronic condition that can impact fertility. That’s why ongoing or worsening pain is worth discussing with a healthcare provider.

Recurrent symptoms? Get Evvy's at-home vaginal microbiome test, designed by leading OB-GYNs.

Are painful periods linked to fertility?

There’s a long-standing myth that period pain means your body is fertile. So, are painful periods a sign of good fertility? The reality is that menstrual pain isn't a reliable marker of good fertility.

Fertility is primarily determined by whether a person is ovulating regularly and whether their reproductive system can support conception and implantation. Regular ovulation (not cramping or pain) is what matters most.

That said, severe menstrual pain can sometimes be linked to conditions like endometriosis or adenomyosis, both of which are associated with fertility problems. In these cases, the pain isn’t a sign of “enhanced fertility” but a sign of a chronic condition that may actually make conceiving more difficult. Endometriosis, for example, can affect fertility through inflammation, scar tissue in the fallopian tubes, ovaries, and uterus, and disrupted embryo implantation.

So, while having painful periods doesn’t mean you’re infertile, it definitely doesn’t mean you’re more fertile. Real signs of healthy fertility include:

- Regular periods

- Signs of ovulation (like changes in cervical mucus or confirmed by tracking methods)

- Balanced hormones (estrogen and progesterone fluctuations that follow a predictable pattern).

Aside from these physical signs, the best way to assess your chances of conceiving is with fertility testing.

Painful periods and the vaginal microbiome

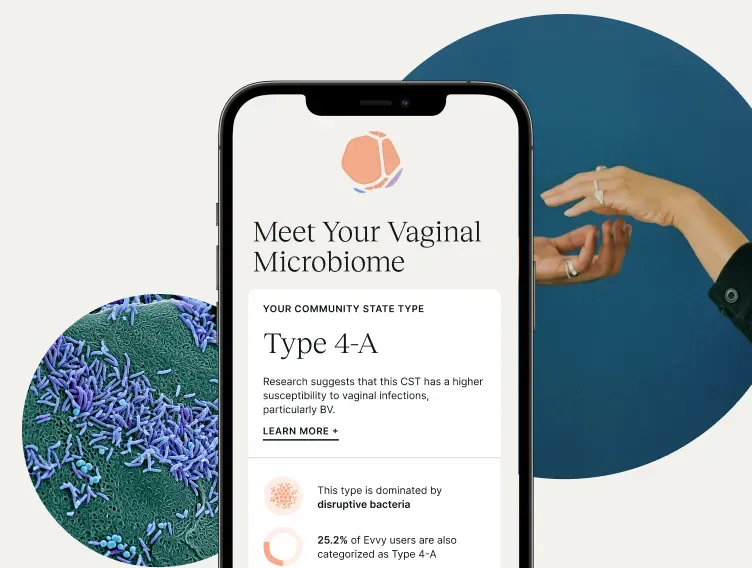

Emerging research highlights that your vaginal microbiome — the community of bacteria, fungi, and other microbes living in your vaginal ecosystem — plays an important role in menstrual health.

When this ecosystem is balanced and dominated by protective Lactobacillus species, it helps regulate inflammation and protect against infection. But when that balance shifts, harmful bacteria can thrive, potentially worsening cramps and pelvic pain.

There's some interesting research suggesting a connection between painful menstrual periods and the vaginal microbiome, although we still need more large-scale studies to understand this relationship fully. Preliminary data show that women who experience more intense dysmenorrhea symptoms (especially those with pain in multiple areas and gastrointestinal issues) often have lower levels of Lactobacillus and higher levels of certain anaerobic bacteria like Prevotella, Atopobium, and Gardnerella during their periods compared to those with milder pain. These types of bacteria are linked to increased inflammation in the genital tract, which might contribute to more menstrual discomfort.

The menstrual cycle brings about natural changes in the vaginal microbiome, and some women may notice fluctuations between a Lactobacillus-dominant state and a more varied, sometimes imbalanced state. This imbalance, known as dysbiosis, has been associated with increased inflammation in the vaginal tissues, which might make cramps and discomfort during periods feel worse. Interestingly, researchers have found differences in the microbial communities in the endometrium and endocervix (the internal, mucus-producing portion of the cervix) of women experiencing dysmenorrhea compared to those with heavy periods. This suggests that our unique microbiomes could actually influence the experience of menstrual pain.

Current medical literature has found a potential link between period pain and changes in the reproductive tract microbiome — specifically, an increase in certain pro-inflammatory bacteria and a decrease in protective Lactobacillus. That said, researchers are quick to point out that more studies are needed to figure out if these changes actually cause pain or if they stem from other inflammatory issues.

It’s also worth mentioning that while imbalances in the microbiome can influence comfort, inflammation, and the risk of infections, researchers are beginning to explore how these microbial shifts may also connect to fertility. So far, studies suggest that the vaginal and endometrial microbiomes play a role in creating a healthy environment for conception and implantation. However, no direct link has been established between menstrual pain–related microbiome changes and fertility outcomes. Instead, the microbiome represents an important piece of the broader picture of reproductive health.

How to manage painful periods

If you experience painful periods, the good news is that there are many strategies (both at home and with medical support) that can make cycles more manageable. The right approach depends on whether your pain is primary or secondary dysmenorrhea, your medical history, and your personal preferences.

At-home strategies

For mild to moderate pain, many women find relief through simple lifestyle changes and natural supports:

- Heat therapy: Using a heating pad or hot water bottle on your lower abdomen can relax uterine muscles and ease cramping.

- Exercise and movement: Light to moderate physical activity, like walking or yoga, may reduce prostaglandin levels and improve blood flow.

- Stress management: Practices like meditation, deep breathing, and adequate sleep can ease muscle tension and improve pain tolerance.

Medications and therapies

If pain is more severe, medical treatments may be recommended:

- NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs): Medications like ibuprofen or naproxen reduce prostaglandin production, directly targeting the cause of cramping.

- Hormonal birth control: Pills, IUDs, patches, or injections can regulate cycles and decrease period pain by thinning the uterine lining.

- Other medical therapies: In cases of endometriosis or adenomyosis, treatment options may involve hormonal therapies, surgical interventions, or specialist-guided care.

When to see a doctor about painful periods

Not all period pain is “normal.” If your cramps are interfering with daily activities, worsening over time, or paired with other symptoms, it’s important to seek medical advice. You should see a doctor if:

- You have chronic pain that doesn’t improve with over-the-counter medications or home remedies.

- You experience pain that extends beyond menstruation, such as during sex or throughout your cycle.

- You have irregular periods.

- Your periods are unusually heavy, prolonged, or accompanied by abnormal bleeding.

- You have additional symptoms like chronic pelvic pain, fatigue, or gastrointestinal issues.

FAQs about painful periods and fertility

Are painful periods a sign of anything?

Painful periods can mean different things depending on the context. In many cases, cramps are simply caused by prostaglandins, the chemicals that help the uterus contract and shed its lining. That alone doesn’t point to fertility, good or bad. However, painful periods can also be a symptom of underlying gynecologic conditions, such as endometriosis, adenomyosis, or fibroids, all of which may impact reproductive health. If your pain is mild and short-lived, it may be considered part of primary dysmenorrhea. But if it’s severe, persistent, or worsening, it’s worth consulting a doctor to rule out chronic conditions.

How do I know if my period is infertile?

Periods themselves aren’t “fertile” or “infertile.” Fertility depends on whether ovulation is happening regularly and whether your reproductive system supports conception. A healthy menstrual cycle usually falls between 21 and 35 days, with signs of ovulation such as cervical mucus changes, a mid-cycle temperature shift, or results from ovulation predictor kits. If your cycles are consistently irregular, extremely painful, or absent, that may be a sign to check in with a healthcare provider. Rather than focusing on period pain as a fertility signal, monitoring ovulation and hormone balance provides much more reliable information.

Is having really intense periods a good sign for fertility?

No, intense period pain isn’t a positive fertility indicator. In fact, severe cramps often signal secondary dysmenorrhea, which is commonly linked to underlying conditions like endometriosis or adenomyosis. Both of these are associated with reduced fertility, not enhanced fertility, because they can disrupt pelvic anatomy, increase inflammation, and interfere with implantation. Fertility is better evaluated by whether you’re ovulating, the regularity of your cycles, and the balance of your reproductive hormones. If your periods are so painful that they disrupt your daily life, it’s important to seek medical advice. Pain alone is never proof of “good fertility.”