What Is HPV? Causes, Symptoms, and How You Get It

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common STI. There are hundreds of different types of HPV, most of which are harmless and won't cause any issues.

Words by Olivia Cassano

Scientifically edited by Dr. Krystal Thomas-White, PhD

Medically reviewed by Dr. Sameena Rahman, MD

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the United States, and most of us will come into contact with it at some point in our lives.

There are hundreds of different types of human papillomavirus, most of which are harmless and won't cause any issues. Some strains of human papillomavirus, however, can cause genital warts and different types of cancer, including cervical, vagina, ovarian, and vulvar cancer. Since there’s no treatment for HPV, awareness and prevention are key — especially for women.

Below, we've put together a comprehensive guide to help shed light on what human papillomavirus is, how it's spread, how it's linked with genital warts and cancer, and the importance of prevention via regular cervical screening and the HPV vaccine.

What is HPV?

There are over 200 different types of human papillomavirus that infect the skin and mucous membranes in the body. Approximately 40 types of HPV can affect the genitals, including the vulva, vagina, cervix, rectum, anus, penis, and scrotum, typically transmitted through sexual contact. Some HPV types cause common warts (such as on your hands and feet), but they aren't sexually transmitted.

HPV is incredibly common — around eight in 10 sexually active people will get a genital HPV infection at some point in their lives. Most genital HPV infections aren't harmful and usually go away on their own without causing any noticeable symptoms. Some types of HPV, though, can lead to genital warts or certain types of cancer.

HPV can be categorized into two groups: low-risk and high-risk. Low-risk HPV usually doesn't cause cancer, but it can cause warts on or around the genitals, anus, mouth, or throat. On the other hand, high-risk types can cause several types of cancer. There are 12 high-risk HPV types, and two of them (HPV 16 and HPV 18) are responsible for most HPV-related cancers.

Symptoms of vaginal HPV

HPV infections don’t typically cause symptoms, so most people will be unaware they have it or experience any issues. However, in some cases, the virus can lead to painless growths or lumps around the vulva and vagina, known as genital warts.

Unfortunately, people with high-risk HPV strains may not experience any symptoms until the infection has progressed to a serious health concern. That’s why regular check-ups are essential in detecting HPV-related abnormalities early through testing. Cervical cancer, in particular, is largely preventable when warning signs are identified early by healthcare professionals (more on that below).

Infections with high-risk HPV strains may not cause symptoms initially, but a prolonged HPV infection can result in precancerous or cancerous lesions, potentially causing common symptoms of gynecological cancers, such as:

- Abnormal vaginal discharge or bleeding

- Digestive issues, difficulty eating, bloating, and abdominal or back pain

- Pelvic pain or pressure

- A more frequent urge to pee and/or constipation

- Itching, burning, pain, or tenderness of the vulva

- Rash, sores, or warts on the vulva.

Keep in mind that symptoms of gynecological cancers can vary, and many of these symptoms can often be caused by other less serious issues. If you notice any of these symptoms, contact your healthcare provider.

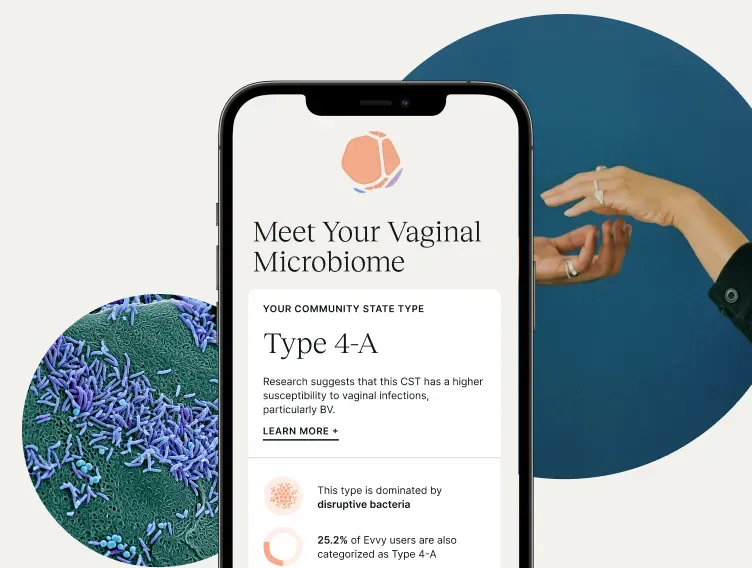

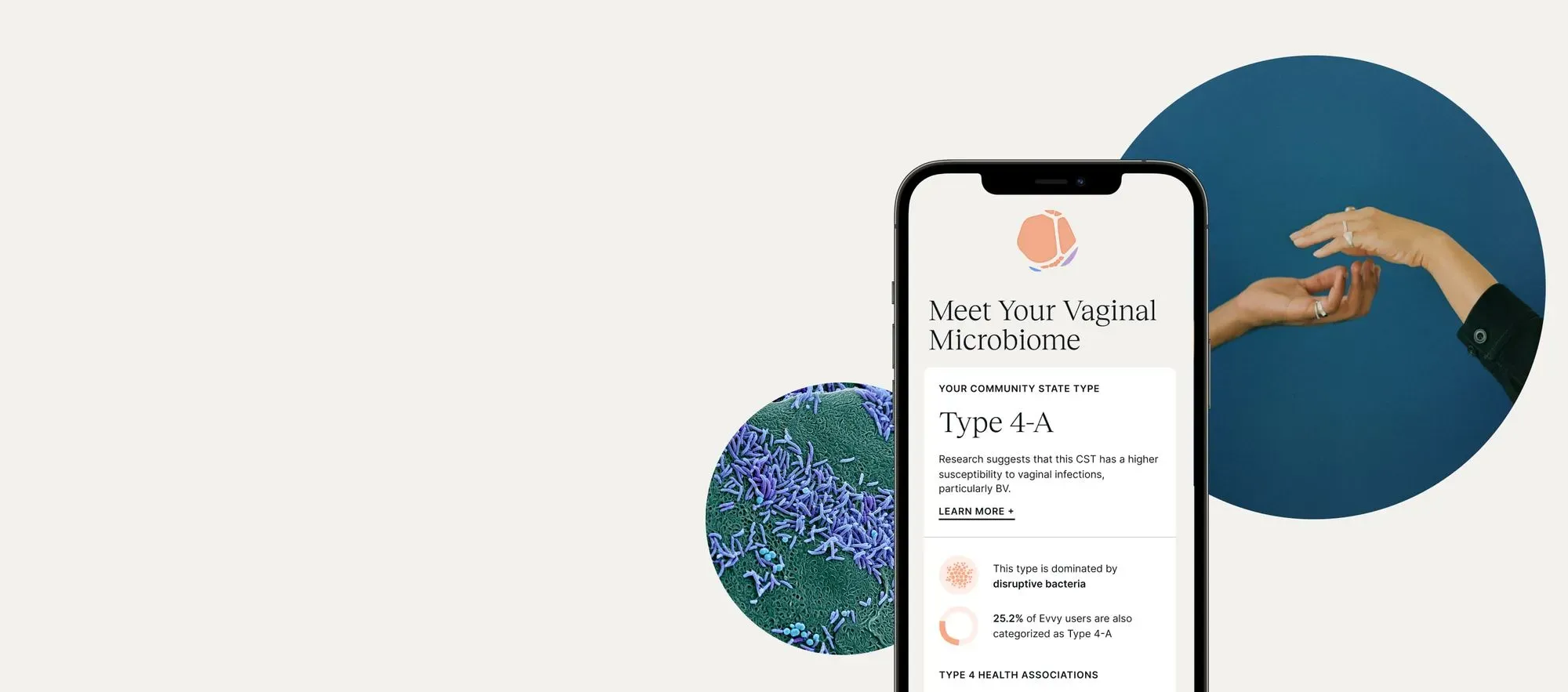

Recurrent symptoms? Get Evvy's at-home vaginal microbiome test, designed by leading OB-GYNs.

How do I know if I have vaginal HPV?

That’s the million-dollar question. HPV doesn’t typically cause symptoms, and unlike most other sexually transmitted infections, there’s no routine test to find out your “HPV status”. Partly because there are hundreds of HPV strains, and not all of them are sexually transmitted. So HPV often flies under the radar, and most people with HPV don’t even know they have the virus unless it manifests as genital warts, or something more serious, such as cervical cancer.

The closest thing to an HPV test would be a cervical cancer screening, commonly referred to as a smear or Pap test. During a Pap test, a small sample of cells is taken from the cervix and analyzed under a microscope to check for cervical cancer or cell changes that may lead to cervical cancer. These tests are offered to women over the age of 21. If you have anal sex, it’s also recommended to do an anal Pap test as well.

Regular Pap tests are a great way to catch any potential health issues early, sometimes even before you start experiencing any symptoms. Although cervical cancer is the only FDA-approved screening test available, it's still important to keep an eye out for any unusual symptoms and talk to your healthcare provider about them. By detecting any problems early, you can give yourself the best chance of effectively treating HPV-related cancers. Additionally, if you're concerned about genital warts, a doctor can check for any bumps or growths on the skin around your genitals.

How do you get HPV?

HPV is mainly spread through sexual activity, like vaginal, anal, or oral sex. But here's the thing: even if you're not doing the whole penetration thing, just close skin-to-skin contact in the genital area can pass it along. Even if someone doesn't have any symptoms, they can still pass HPV to others during sex. So, whether you've been with just one person or have several sexual partners, if you're sexually active, you can get HPV. The tricky part is that symptoms might not pop up until years after exposure, so it's tough to know when it first appeared.

HPV and genital warts

Among the multitude of HPV strains, some (types 6 and 11, specifically) are responsible for causing genital warts, which are one of the most recognizable symptoms of HPV infection. Genital warts appear as small, flesh-colored bumps in the genital and anal areas. They can be big or small, flat, or in clusters like a cauliflower.

There’s no swab or blood test to diagnose genital warts. Your healthcare provider will usually diagnose warts by looking at your genitals. Fortunately, the HPV strains responsible for genital warts are considered low-risk, so they aren’t dangerous and don’t lead to cancer.

While genital warts are harmless and don’t pose any risk to your health, genital warts can cause discomfort, itching, and psychological distress.

Sometimes, genital warts may go away on their own because your immune system fights off the infection, but sometimes they can become larger, more uncomfortable, or even multiply over time. It's best to get rid of them to reduce the risk of spreading an HPV infection since active outbreaks are more contagious. However, it's important to note that treatment won't cure genital warts.

There are different ways to remove genital warts, and you may need multiple sessions to clear them. While undergoing treatment, it's best to abstain from sexual activity. Your healthcare provider might suggest freezing them off, using a prescription topical medication, or removing them with surgery.

Remember, treatment for genital warts won't rid you of HPV. Even after wart removal and without any active outbreaks, you can still transmit HPV to others.

Does HPV cause cervical cancer?

Although most HPV infections go away on their own, some types of HPV could lead to certain types of cancer. Persistent infection with these high-risk strains can increase the risk of developing various cancers, including cervical, vaginal, vulvar, anal, penile, and throat cancer. Cancer often takes years, even decades, to develop after a person gets HPV.

HPV and cervical cancer

Nearly all cervical cancer cases are caused by HPV. Luckily, routine cervical cancer screening and Pap tests can prevent cervical cancer by detecting and removing precancerous or abnormal cells before they develop.

Pap tests look for cervical cell changes that could lead to cancer, known as cervical dysplasia. Depending on the severity, dysplasia can be categorized as mild, moderate, or high grade.

Mild or low-grade dysplasia tends to go away as your body clears the viral infection. However, if the HPV infection persists, it can lead to precancers such as moderate and high-grade dysplasia. These precancers require treatment to prevent them from developing into cancer.

When high-risk HPV infects cervical cells, it disrupts their normal function and how they replicate. Although the immune system typically finds and controls these infected cells, sometimes they persist and continue to grow. This eventually leads to the formation of a region of precancerous cells that can turn into cancer if left untreated.

It can take five to 10 years for HPV-infected cervical cells to develop into precancers, and about 20 years to develop into cancer.

It's understandable to feel worried if you've been diagnosed with moderate or high-grade dysplasia. Please know that not all precancers become cancerous, and researchers are working hard to identify biomarkers that can predict the likelihood of precancers becoming cancerous.

If you're dealing with moderate or high-grade dysplasia, your healthcare provider will be there to support you and discuss your treatment options.

For a minority of women, HPV won’t go away on its own. Several factors increase the risk that an HPV infection will be long-lasting and lead to precancerous cervical cells:

- having a very aggressive HPV type, particularly HPV 16 or HPV 18

- smoking

- being immunocompromised or having human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

HPV treatment

There’s no treatment for HPV, but there are a few things you can do to help prevent HPV or keep it from negatively impacting your health:

- Get vaccinated: the HPV vaccine (Gardasil) is a safe and effective way to protect yourself against diseases caused by HPV. The vaccine is recommended for certain age groups and can even prevent up to 90% of HPV-related cancers and genital warts.

- Don't skip your routine Pap tests: as uncomfortable as they are, Pap tests are an incredibly effective way to prevent cervical cancer. Remember: prevention is better than treatment.

- Practice safe sex: using condoms and dental dams can also help lower your chances of getting HPV and other STIs, but it's important to remember that they may not fully protect against the virus.

Although there is no treatment for the virus itself, there are treatments available for the complications HPV can cause, such as genital warts or cervical precancer treatment.

Who should get the HPV vaccine?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends HPV vaccination for:

- All boys and girls at age 11 or 12 years (and as early as 9)

- Everyone through age 26 years old, if they’re not vaccinated already

The HPV vaccine isn't usually recommended for adults over 26, but if you're 27-45 and haven't been vaccinated yet, it's worth chatting with your healthcare provider to see if it might be a good option for you. While the benefits may be less for those in this age range, it's always better to be safe than sorry.

It's also worth noting that if you're in a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship, you're less likely to get a new HPV infection. However, it's important to be aware of the risks if you're starting a new relationship and are sexually active.

FAQs

What is HPV caused by?

Human papillomavirus is caused by infection with the human papillomavirus, a group of more than 100 related viruses. It is primarily transmitted through skin-to-skin contact, most commonly during sexual activity. HPV infections can affect the skin or mucous membranes and are often spread through vaginal, anal, or oral sex. While many types of HPV are harmless and clear on their own, some strains can lead to health problems, such as genital warts or even cancer, particularly cervical, throat, and anal cancers.

What happens if you have HPV?

HPV infections are quite common and don't cause any serious health problems most of the time. Your immune system can usually fight off an HPV infection within a year or two. However, people with weakened immune systems may be at a higher risk of developing health problems related to HPV, such as genital warts or cervical cancer. If you’re a sexually active woman or AFAB person, it’s really important to get routine cervical cancer screening for this reason.

Is HPV still considered an STD?

Yes, human papillomavirus is a sexually transmitted disease (STD) because it’s most commonly transmitted throughs sexual contact. It’s actually the most common STD.

Does female HPV go away?

Currently, there’s no cure for an existing HPV infection. In most cases, though (9 in 10, according to the CDC) an HPV infection will go away on its own within a couple of years without causing any health problems. There are, however, treatments available for problems caused by HPV, such as genital warts.