Is Lactobacillus Iners Helping or Harming Your Microbiome?

Learn what detection of Lactobacillus iners means, whether it shows up in urine, its role in preventing UTIs, and what drives its overgrowth.

Words by Olivia Cassano

Scientifically edited by Dr. Krystal Thomas-White, PhD

Medically reviewed by Dr. Christine Vo, MD

Lactobacilli are often heralded as the local heroes of the vaginal microbiome. But, it turns out, not all Lactobacillus bacteria are created equal, especially when it comes to Lactobacillus iners (L. iners).

Lactobacillus iners is a strain of bacteria that seems to act “protective” when it's around other protective bacteria, and problematic when it's around disruptive bacteria in the vaginal microbiome.

It also tends to be found in higher levels when your vaginal microbiome is transitioning, whether that’s due to the normal fluctuations with the menstrual cycle, or if the microbiome is transitioning in or out of a dysbiotic state like bacterial vaginosis (BV).

While the research on Lactobacillus iners is still emerging, we’re covering everything you should know about the most finicky species of all the lactobacilli found in the vaginal microbiome and what it means if L. iners dominates your microbiome.

Lactobacilli: the local heroes of the vaginal microbiome

Let’s start with the basics: Lactobacillus is a genus of bacteria found in the human body in places such as the gut, skin, and urinary tract.

More relevant to us, Lactobacilli are often the dominant species of bacteria found in the vaginal microbiome. This is because it helps maintain vaginal health in a variety of ways. They create lactic acid to keep the vaginal pH in the ideal range, block out bad bacteria, make natural antibiotics, and even help reduce inflammation.

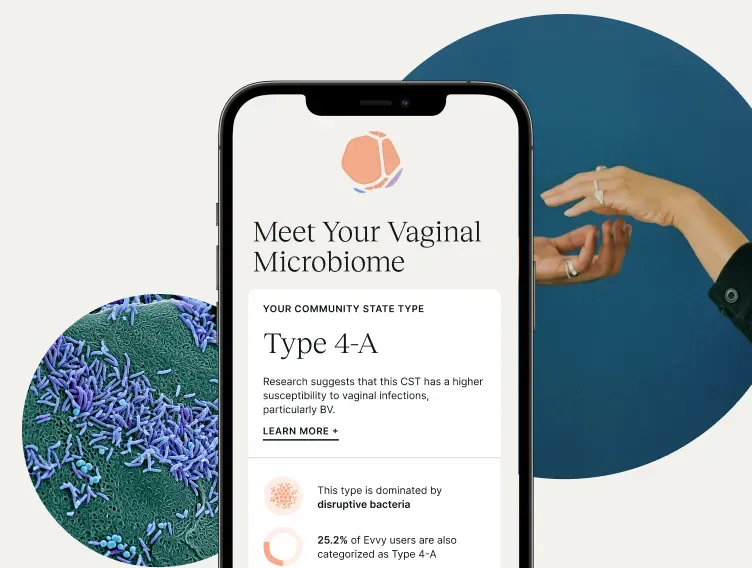

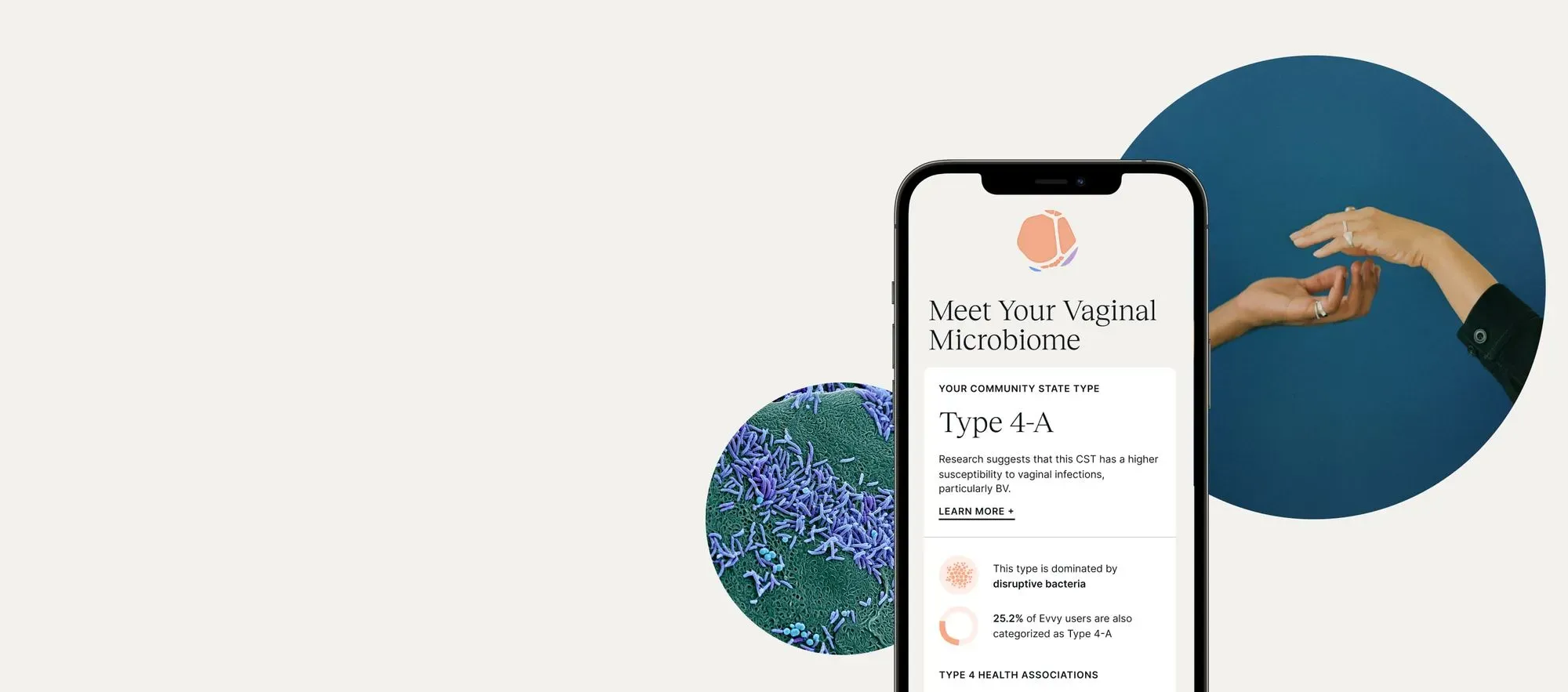

Recurrent symptoms? Get Evvy's at-home vaginal microbiome test, designed by leading OB-GYNs.

What is Lactobacillus iners?

Lactobacillus iners is a species within the Lactobacillus genus. Despite being the most common microbe found in the vaginal microbiome, it was only discovered in 1999 (yes, research into vaginal health is that behind) — making Lactobacillus iners the official Gen Z-er of the Lactobacillus clan.

It’s also the type of Lactobacillus that characterizes Community State Type (CST) III vaginal microbiomes, the CST that seems to be most susceptible to changes (both positive and negative).

What makes Lactobacillus iners different from other Lactobacillus species?

Several things.

It’s hard to detect under a microscope

Lactobacillus iners can literally look physically different from other Lactobacilli under a microscope. This can make it difficult to identify L.iners with diagnostic processes that rely on the shapes of microbes to determine if someone has an infection.

A classic example of this is the Nugent score, a diagnostic process that came about in the early '90s. To determine someone’s Nugent score, a clinician will look at a stained vaginal smear under the microscope and count the number of different types of cells present (based on their shape) to determine the patient’s Community State Type.

Despite being the “go-to” test to diagnose bacterial vaginosis, the Nugent isn’t very good at picking up trickier-to-spot microbes, such as Lactobacillus iners. That means that someone with L. iners might get a worse Nugent score when they’re healthy.

It relies on other nutrients from the vaginal microbiome to survive

Compared to other vaginal Lactobacillus species, L. iners has more genes for acquiring outside nutrients. This means it produces fewer of its own nutrients and instead relies on scavenging nutrients from its environment (the vaginal microbiome) to survive.

Lactobacillus iners is sometimes referred to as the “ultimate survivor” of the vaginal microbiome — given its ability to scavenge for a variety of nutrients, it often survives when other microbes don’t (which may be why we see it during times of transition, like after taking an antibiotic).

It doesn’t keep the vaginal environment as acidic as other Lactobacilli

Lactobacillus iners is the only major vaginal lactobacilli that doesn’t produce any D-lactic acid. Always the rebel, it also produces lower amounts of hydrogen peroxide.

Molecules like D-lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide give other Lactobacillus their protective status because lactic acid and hydroperoxide work to keep disruptive bacteria at bay within the vaginal microbiome.

Therefore, Lactobacillus iners has a reputation for being less protective compared to the rest of the L-squad.

Does Lactobacillus iners cause bacterial vaginosis?

Now that you know Lactobacillus iners steals to survive (don’t knock the hustle) and produces few protective molecules, you may be wondering if it makes bacterial vaginosis more likely.

Like most things with the vaginal microbiome, the answer is complicated. There isn’t any evidence that proves Lactobacillus iners causes bacterial vaginosis on its own. However, there is evidence of L. iners being present within the vaginal microbiome when a bacterial vaginosis infection is at play (which is less common with other species of Lactobacilli).

So you’re not alone if your Evvy results show higher amounts of disruptive bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis and higher levels of L. iners.

It’s often found during transitions in your vaginal microbiome

Bacterial vaginosis isn’t the only vaginal storm Lactobacillus iners sticks around for. An L. iners-dominated microbiome is more prone to big shifts than an L. crispatus-dominated one. For example, having L. crispatus makes you less likely to have disruptive microbes present, but the same cannot be true for L. iners. Studies show L. iners stays put when shifts take place in your vaginal microbiome.

L. iners is often found when someone is transitioning in OR out of an infection like bacterial vaginosis, a yeast infection, or sexually transmitted infections.

Studies have shown that it's common for the levels of L. crispatus and L. iners to fluctuate throughout the menstrual cycle. Specifically, higher levels of L. iners are often present during your period, when the pH of your vagina is elevated due to the presence of menstrual blood, which has a higher pH than in a healthy vaginal microbial environment. Like a "spring break" for our rebellious microbes, but it happens every month!

Other species of Lactobacilli (like L. crispatus) work hard to keep the vaginal environment acidic (and therefore stable) by not letting other, more disruptive microbes overproduce. L. iners, on the other hand, seems more likely to ride the waves of a shift in vaginal flora, making it resilient in its own way.

Why does this happen? Well, L. iners simply prefers to get along with other microbes rather than to enforce rules. So, it’s more likely to stick around: infection or no infection.

And while L. iners may get the award for “most chill,” this also means it’s probably not going to kick the microbes causing a ruckus out or worse, stop them from trashing the house.

Why would I have Lactobacillus iners in my vaginal microbiome?

If you have L. iners present, you are far from alone. The study that first introduced the concept of vaginal CSTs back in 2011 (we told you research on vaginal health is lagging) highlighted that 83.4% of women have detectable L. iners in their microbiomes. However, only 34.1% of these women were in CST III or a vaginal environment that is dominated by L. iners.

This study also suggests that when Black or Hispanic women have Lactobacillus-dominated microbiomes, it’s usually L. iners. Why? Unsurprisingly, this is another important question that needs better research.

Is there a link between Lactobacillus iners and sex?

A recently published study looked into lifestyle factors and L. iners abundance. It loosely suggests that having “two or more sexual partners in the last 12 months” may be linked to higher levels of L. iners. This makes sense because we know that sex, particularly sex with a new partner, can alter the vaginal microbiome and that L. iners is usually stable in times of flux. So it could be that L. iners dominance is simply a sign that your microbiome is changing.

In addition to its “multiple sexual partners” finding, the study shares that condom use is the biggest influencing factor on L. iners abundance. Those who used condoms were the least likely to have microbiomes with high levels of L. iners. This is understandable, if not unsurprising, given that condom use also helps protect against bacterial vaginosis.

The same study mentioned above also found an interesting relationship between higher levels of L.iners and the microscopic detection of Candida (the fungus that causes yeast infections) on vaginal smears.

Having said all of this, we want to stress that the jury is still out on whether L. iners dominance is necessarily a bad thing. As we said, L. iners is the “ultimate survivor” of the vaginal microbiome, so its presence could simply be a signature of a change.

What should I do if I have Lactobacillus iners in my vaginal microbiome?

Don’t be alarmed, especially if you aren’t experiencing any uncomfortable symptoms. L. iners dominance, or being in CST III, doesn’t mean your vaginal microbiome is in dysbiosis.

L. iners is a bacterium that can be affected by chance. Things are likely to be fine if it’s consistently surrounded by protective bacteria. However, if disruptive bacteria come around, having a microbiome dominated by L. iners means you may become more susceptible to disruptions in the vaginal microbiome.

By this logic, if you slot into Community State Type III, it won’t hurt to be a bit more mindful when it comes to your health. This includes using protection when having sex, only cleaning your vagina and vulva with water, ditching the douche, and passing on feminine hygiene products and sex aids that promise to “heat” things up, figuratively and chemically (though we know it can be tempting to try the tingly lubes).

Given that L. iners is often found during times of transition and is susceptible to changes, it may be helpful to keep closer tabs on your microbiome to make sure it doesn’t start to slip into vaginal dysbiosis.

Finally, you can work on transitioning your vaginal microbiome to a more protective state. An Evvy test will help you identify if you have L. iners in your vaginal microbiome, and the results will come with a plan (and a free session with one of our vaginal health coaches) to help increase the protective bacteria and your vaginal microbiome.

FAQ

Is Lactobacillus iners good or bad?

Lactobacillus iners is neither inherently good nor bad. It's unlikely to cause issues if it is consistently surrounded by protective bacteria. However, if disruptive bacteria come around, having a vaginal microbiome dominated by L. iners may make you more susceptible to dysbiosis. It's important to note that there is still uncertainty regarding whether L. iners dominance is necessarily negative.

What does it mean when Lactobacillus iners are elevated?

When the levels of L. iners are high, it means that there's more of this particular type of Lactobacillus in the vaginal microbiome than usual. Lactobacillus iners is a kind of bacteria that normally lives in the vagina and helps maintain its acidic environment, which is important for keeping harmful bacteria in check. However, unlike some other types of Lactobacilli, L. iners isn't as good at keeping the vaginal environment stable and protected. When there are high levels of L. iners, it could suggest that the vaginal microbiome is disrupted, and there may be an increased risk of issues like bacterial vaginosis or other infections, as this species can coexist with or even help the growth of bad bacteria.

What does it mean if you have Lactobacillus iners in your urine?

Finding Lactobacillus iners in your urine is generally normal, especially for women, and isn’t a sign of infection or illness. L. iners is one of several Lactobacillus species commonly found in the vaginal and urinary tracts, where they play a key role in maintaining a healthy microbiome. Its presence usually doesn’t cause symptoms or indicate any imbalance, particularly when other beneficial bacteria are also present. Because of the close connection between the vaginal and urinary microbiomes, it's common for vaginal bacteria like L. iners to show up in urine samples. While L. iners is sometimes considered a "transitional" species that may offer less protection than others like L. crispatus, it is still part of a normal, healthy microbial community. So, seeing L. iners in urine is not typically a cause for concern on its own — it’s just one piece of the bigger picture of vaginal and urinary health.

Does Lactobacillus iners prevent UTIs?

Research suggests that while L. iners is often found in healthy and transitional vaginal environments, it’s not strongly linked to UTI prevention. In general, Lactobacillus helps prevent UTIs by blocking harmful bacteria, producing antimicrobial compounds like hydrogen peroxide, and supporting the immune system. However, L. iners produces less hydrogen peroxide and shows weaker anti-pathogen activity compared to protective species like L. crispatus or L. jensenii. In contrast, maintaining or restoring L. crispatus (which can be found in Evvy Women’s Complete Probiotic) has been shown in clinical trials to significantly reduce UTI recurrence, making it a more effective target for probiotic therapies.

What causes overgrowth of Lactobacillus iners?

An overgrowth of Lactobacillus iners usually happens when the vaginal microbiome is in transition or recovering from a disruption. It’s not typically harmful, but it’s less protective than other good bacteria like Lactobacillus crispatus. L. iners often becomes dominant after treatment for bacterial vaginosis or yeast infections, during hormonal changes like your period, or when vaginal pH shifts — such as after using certain products or having sex. Rather than being the root cause of problems, L. iners overgrowth often signals that the microbiome is in flux and trying to rebalance after a change, infection, or loss of stronger protective species.

How to get rid of Lactobacillus iners?

You don’t always need to “get rid of” Lactobacillus iners — it’s often part of a transitional vaginal microbiome and isn’t harmful on its own. However, if L. iners is dominant and you're dealing with symptoms like discharge, odor, or recurrent infections, a provider may recommend steps to help shift your microbiome toward more protective species like Lactobacillus crispatus. This might involve prescription treatments to address any underlying infection, followed by probiotics that support healthy bacteria. Avoiding disruptive products like douches or high-pH lubricants can also help maintain balance. An Evvy test can identify L. iners overgrowth and connect you with a provider who can create a personalized plan. Always work with a healthcare provider before trying to change your vaginal microbiome — L. iners isn’t inherently bad, but if it’s crowding out more protective species, there may be ways to encourage a healthier microbial balance.

What antibiotics are used to treat Lactobacillus iners?

There aren’t any antibiotics specifically designed to target Lactobacillus iners, and usually, its presence doesn’t require treatment. However, if L. iners is dominant alongside symptoms or harmful bacteria, such as in recurrent bacterial vaginosis, your healthcare provider may prescribe antibiotics to address the overall imbalance. Common antibiotics for bacterial vaginosis include clindamycin or metronidazole, which help reduce harmful bacteria but can also affect good bacteria, including L. iners. In some cases, tinidazole or secnidazole may be used for recurrent infections. Since L. iners often persists or returns after treatment, providers might recommend following antibiotics with vaginal probiotics to encourage the growth of more protective species like Lactobacillus crispatus. It’s important to consult a healthcare provider to choose the best treatment based on your individual symptoms and microbiome.