Can I Get a Vaginal Infection During Pregnancy?

Is it still possible to get a vaginal infection when you’re pregnant? Learn about common infections and safe treatment options for expecting moms.

Words by Olivia Cassano

Scientifically edited by Dr. Krystal Thomas-White, PhD

Medically reviewed by Dr. Christine Vo, MD

Expecting a baby is definitely an exciting and life-changing event, but let’s face it, pregnancy can also be quite uncomfortable. And the last thing you want added to the mix is a vaginal infection.

During pregnancy, your body is going through a lot of changes that can impact your vaginal microbiome. Fluctuating hormone levels, vaginal mucus production, and lifestyle changes can all impact your vaginal flora.

While some women may experience vaginal infections during pregnancy, there is always a chance of developing new vaginal infections. In fact, in some cases, your risk may even increase (more about that below).

Five different vaginal infections can affect pregnant women:

- Group B Strep

- Vulvovaginal candidiasis (vaginal yeast infections)

- Bacterial vaginosis (BV)

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs)

- Aerobic vaginitis (AV).

If you have a vagina, chances are you've had to deal with an infection at some point. But have you ever wondered how pregnancy can affect your risk of vaginal problems, and what options you have for treatment? Let's dive in and explore what we know about the different types of vaginal infections during pregnancy.

Group B strep

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is a type of bacteria that lives in your gut and genitals. It usually doesn't cause any problems, but sometimes it can lead to serious infections. GBS is found in 10-30% of pregnant women, but this varies based on ethnicity and location. In pregnant women, GBS can cause urinary tract infections, postpartum and intrauterine infections, and can disrupt the vagina's natural balance, leading to yeast infections.

There is a small risk that GBS can lead to pregnancy complications such as premature birth, premature rupture of membranes (PROM), and neonatal infection. However, doctors proactively screen for GBS in pregnant women around 36-37 weeks of pregnancy. If you test positive, antibiotics will be given during labor to prevent passing the infection to the baby.

Research has looked at using probiotics as an alternative to antibiotics. Some types of probiotics have been found to limit the growth of GBS and may reduce the risk of transmitting it to the fetus. However, probiotics are still being studied and not yet recommended as a treatment for GBS by ACOG.

While GBS is usually harmless in non-pregnant individuals, it can interact with other bacteria, such as Candida albicans, which causes yeast infections, and bacteria associated with urinary tract infections and bacterial vaginosis. GBS can help these pathogens thrive and may play a role in setting the stage for other bacteria to thrive as well.

Recurrent symptoms? Get Evvy's at-home vaginal microbiome test, designed by leading OB-GYNs.

Yeast infections

Yeast infection, also known as vulvovaginal candidiasis, are is caused by an overgrowth of Candida yeast, a fungus that naturally lives in your body. They’re a super common vaginal infection, and 75% of women will experience a yeast infection at least once in their lifetime. The most common symptoms of a yeast infection are:

- Vulvar and vaginal itching redness, or soreness

- Unusual vaginal discharge that is white and clumpy, like cottage cheese

- Pain during sex

- A burning sensation when you pee.

Yeast infections during pregnancy are pretty common. When you're pregnant, the increased estrogen levels may make you more likely to develop yeast infections. Pregnancy can cause your immune system to decrease, your vaginal mucosa to have more glycogen, and your estrogen production to increase. Unfortunately, these are all things that Candida loves.

A yeast infection is usually nothing more than an itchy nuisance, but during pregnancy, it can cause PROM, preterm labor, and intraamniotic infection if left untreated.

Luckily, you can treat yeast infections with antifungal creams. A small study of 78 pregnant women found that Lactobacilli probiotics were useful in reducing yeast infection symptoms and limiting recurrence.

Even if you've had a yeast infection in the past, it's best to check with your doctor beforehand as some medications may not be suitable for use during pregnancy.

UTIs and bacterial vaginosis

UTIs and bacterial vaginosis happen when harmful bacteria overgrow in your urinary tract or vaginal microbiome, respectively. Both can lead to dysbiosis, which is when the normal balance in the vagina is disrupted and the number of good bacteria (like Lactobacilli) decreases.

Maintaining a healthy vaginal microbiome dominated by Lactobacillus is crucial during pregnancy because it helps protect both the parent and the fetus. Dysbiosis can increase the risk of preterm birth and PROM. Vaginal dysbiosis accounts for around 50% of spontaneous preterm births.

Some studies also found that women who give birth prematurely often have lower levels of a protective Lactobacillus called L. crispatus, and higher levels of BV-associated bacteria. This can increase the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and chorioamnionitis, which is an infection of the placenta and amniotic fluid. Some experts and doctors are suggesting routine screening and management of bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy check-ups to help prevent these risks.

The good news is that when UTIs and bacterial vaginosis are diagnosed early, they're generally easy to treat with a round of antibiotics.

While there is evidence suggesting that a diverse vaginal microbiome may increase these risks, it's important to remember that this may not be true for everyone. More research is needed to fully understand the connection between microbiomes and preterm birth. Just keep in mind that correlation doesn't always mean causation!

Aerobic vaginitis

Aerobic vaginitis (AV) is a vaginal infection caused by an excess of aerobic microbes. This is different from bacterial vaginosis, which is caused by anaerobic bacteria (meaning they don’t need oxygen to survive). Both share a similarity in that they tend to be the result of dysbiosis, and AV is often mistaken for bacterial vaginosis.

Some common symptoms of AV are yellow or yellow-green discharge accompanied by a foul-smelling odor, vaginal redness, and a stinging or burning sensation.

During pregnancy, AV is associated with an increased risk of premature delivery, PROM, stillbirth, as well as neonatal and maternal infections. It’s estimated that 4-8% of pregnant individuals develop AV.

How to prevent vaginal infections during pregnancy

Since the hormone changes caused by pregnancy can make you more susceptible to vaginal infections, it’s not always possible to prevent them entirely. But, you can do a few things to look after your vaginal microbiome as much as possible.

- Track your discharge. Changes in vaginal discharge are normal during pregnancy, so ask your OB-GYN or healthcare provider what you should look out for. Abnormal-looking and foul-smelling vaginal discharge is often a telltale sign that something’s up, down there.

- Stay up to date with pregnancy check-ups. Throughout your pregnancy, your doctor will screen for infections and make sure both you and the baby are healthy.

- Keep practicing safe sex. If you’re having sex throughout your pregnancy, keep using barrier methods like condoms and dental dams — especially if you have several sex partners or sleep with a new sexual partner. The goal here isn’t to prevent pregnancy (it’s a bit too late for that) but rather to prevent unwanted pathogens from entering your microbiome and reduce the risk getting a sexually transmitted infection (STI).

- Skip the feminine hygiene products. Despite the convincing marketing, washes, douches, and deodorants can disrupt your microbiome and put you at an increased risk of dysbiosis. Your vagina is self-cleaning and during pregnancy, it’s especially good at keeping out unwanted bacteria. To wash your vulva, you only need some warm water (and hypoallergenic soap at a push).

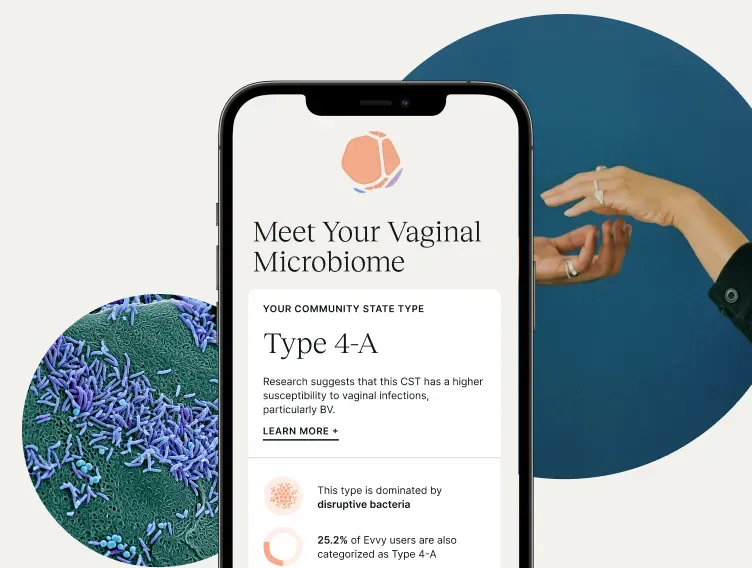

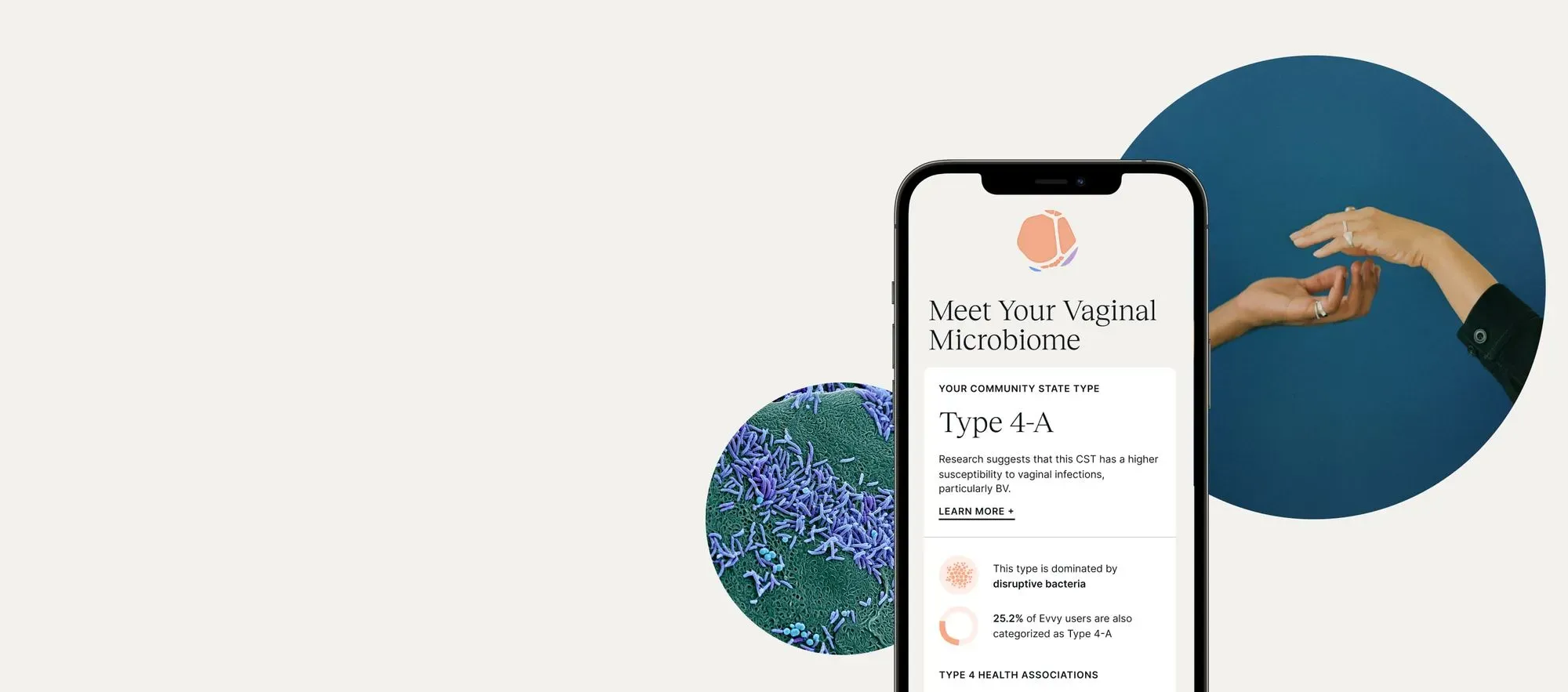

- Monitor your vaginal microbiome with Evvy. An Evvy membership lets you track changes in your vaginal microbiome overtime, giving you an in depth look at the protective and disruptive microbes and providing you with a personalized care plan to shift your microbiome back into a protected state.

FAQ

Can a yeast infection hurt my unborn baby?

Getting a yeast infection during pregnancy usually won't harm your baby, but in rare cases there is a very small risk of PROM, preterm labor, and intraamniotic infection if left untreated. It's important to get it treated quickly to feel better and avoid any problems. If you don't get treatment, there's also small chance of passing the infection to the baby during birth, but don't worry, it's treatable. Just make sure to talk to your healthcare provider for the best advice on how to take care of yourself and your baby.