Understanding Gardnerella Vaginalis

Gardnerella vaginalis can be linked to bacterial imbalances, sexual activity, and hygiene habits. Learn how you can get it and ways to lower your risk.

Words by Olivia Cassano

Scientifically edited by Dr. Krystal Thomas-White, PhD

Medically reviewed by Dr. Christine Vo, MD

If you’ve ever had bacterial vaginosis (BV), you may be familiar with Gardnerella vaginalis, a type of bacteria that’s often associated with vaginal dysbiosis (an imbalance of the normal vaginal flora). Gardnerella is present in 98% of women with symptomatic bacterial vaginosis.

But what is Gardnerella vaginalis? Is there more than one type? Why can Gardnerella wreak havoc on my vaginal health? And do I always need to get rid of Gardnerella if it’s in my vaginal microbiome?

Below, we go over what we do know about Gardnerella, including Gardnerella vaginalis, based on the current research.

What is Gardnerella?

Gardnerella is a bacteria often found in the vaginal microbiome. Though Gardnerella can sometimes coexist peacefully with other microbes, it's an opportunistic bacterium. Under the right conditions, it can cause vaginal discomfort or contribute to a vaginal infection, like bacterial vaginosis (which is the most common vaginal infection among reproductive-age women).

What causes Gardnerella?

Like many other aspects of vaginal health, researchers still don’t understand what causes Gardnerella bacteria to overgrow, and the exact downstream issues it causes for people with vaginas. So, how do you get Gardnerella vaginalis?

Gardnerella vaginalis is a naturally occurring anaerobic bacteria found in the vaginal microbiome of many people with vaginas. On its own, it’s not harmful — in fact, it’s part of what’s considered a normal microbial community. But when something throws off the balance of the vaginal microbiome, Gardnerella can overgrow and become the dominant species. This overgrowth is one of the key features of bacterial vaginosis (BV), a common vaginal infection that can cause symptoms like a strong fishy odor, thin grey discharge, and irritation.

It’s important to know that you can’t “catch” Gardnerella from another person like a traditional sexually transmitted infection (STI). While sexual activity — especially with new or multiple partners — has been linked to an increased risk of bacterial imbalance, Gardnerella vaginalis isn’t classified as an STI by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). So even though sex can influence the microbiome, the presence of Gardnerella isn’t a sign of infection from a partner.

Researchers are still uncovering exactly what triggers Gardnerella to overgrow, but several lifestyle and biological factors appear to increase the risk, including:

- Sexual intercourse (with multiple sex partners or a new sex partner)

- Hormonal fluctuations (e.g., from birth control, pregnancy, and/or menopause)

- Your period

- Smoking cigarettes

- Chronic stress

- Douching.

Recurrent symptoms? Get Evvy's at-home vaginal microbiome test, designed by leading OB-GYNs.

What are the different Gardnerella species?

Gardnerella vaginalis gets most of the airtime because it’s most common, but did you know there are other species within this group? Currently, there are four named species, which are all closely related:

Researchers have been investigating the connection between Gardnerella vaginalis and bacterial vaginosis since 1953, but it was only in 2019, with the application of whole genome sequencing, that we discovered there were multiple different species of Gardnerella, and the newer species got their names.

This matters because not all Gardnerella are the same. Science is still figuring out what each of these new species does in the vagina and how they affect overall vaginal health.

Most of the research up to 2019 uses the term Gardnerella vaginalis, but with the discovery of these new species, it is unclear how much of this research can be attributed to a specific species rather than the genus overall.

What does Gardnerella do in the vagina?

Gardnerella is an “indicator species,” meaning it is often associated with bacterial vaginosis.

Gardnerella is present in 98% of women with symptomatic bacterial vaginosis, but it can also be found in 55% of asymptomatic women. This means that you can be in Community State Type IV, can be Gardnerella dominant, and not experience symptoms.

That being said, Gardnerella dominant microbiomes are more at risk for developing bacterial vaginosis and its typical symptoms, including:

- Abnormal vaginal discharge that is thin, gray or white

- A strong or fishy vaginal odor.

- Vaginal itching or discomfort.

Is Gardnerella the same as BV?

Back in the 1950s, researchers thought that Gardnerella vaginalis alone might cause bacterial vaginosis. In some older studies linking Gardnerella vaginalis bacteria and bacterial vaginosis, the condition is called "non-specific vaginitis," which is a term not commonly used anymore, but you may come across it in an internet search rabbit hole (we’ve been there too).

However, many studies since then have been trying to figure out which specific species of Gardnerella might be causing symptoms and which might be hanging out peacefully in the vagina — no single species of bacteria is universally present in all vaginas with bacterial vaginosis, making it impossible that Gardnerella is the sole cause of BV.

Is Gardnerella responsible for your vaginal symptoms?

Gardnerella and vaginolysin

We do know that Gardnerella microbes have some special features or genes that could be contributing to symptoms (in science-speak, these genes are called pathogenicity genes). Specifically, Gardnerella can produce a toxin called “vaginolysin.”

In experiments, vaginolysin can directly damage the vaginal epithelial cells (the cells that line your vagina). However, this can only happen if vaginolysin reaches the bottom side, as opposed to the surface, of the cells.

Here’s where things get interesting: some Gardnerella strains found in bacterial vaginosis do not have the genes required to produce vaginolysin, or those genes are mutated somehow. Does that mean some Gardnerella could be less harmful or even neutral or protective?

Well, we’re still trying to map out which Gardnerella species and strains produce an active version of this gene and which don’t.

To further complicate things, not all Gardnerella produce the same amount of vaginolysin, and other microbes, like Lactobacilli bacteria, can suppress vaginolysin production.

So, although we know vaginolysin exists, that it can theoretically damage the lining of the vagina if it reaches the right place, and some Gardnerella might produce it given the right conditions, it isn’t a one-size-fits-all explanation of why Gardnerella vaginalis is associated with bacterial vaginosis.

Gardnerella and sialidase

Another pathogenicity gene Gardnerella produces is sialidase. Sialidase is an enzyme that breaks down the mucus layer covering the vaginal wall. We know that levels of sialidase in vaginal secretions are associated with a shift from a Lactobacillus dominant microbiome to a more diverse microbiome.

Sialidase and biofilms

If you’ve ever dealt with chronic bacterial vaginosis, yeast infections, or any vaginal infections, you may have heard of a biofilm.

Biofilms are three-dimensional structures that bacteria form that make it hard to clear an infection, including vaginal infections like bacterial vaginosis.

It is hypothesized that sialidase is needed to break down the mucus layer and produce biofilms.

Gardnerella is not the only bacteria that can produce sialidase: Prevotella and Mobiluncus can as well. And, different species and strains of Gardnerella produce varying amounts of sialidase.

Gardnerella and biofilms

This leads us to the last of the three Gardnerella pathogenicity genes we are going to cover: biofilms. As we said above, biofilms are 3D clumps of bacteria that make it super hard to get rid of bacterial vaginosis with just antibiotics alone, leading to persistent vaginal symptoms like excessive vaginal discharge and odor.

Gardnerella makes excellent biofilm scaffolding and it can grab onto the lining of the vagina. Gardnerella biofilms also make great homes for other bacteria like Prevotella, Fannyhessae, and Mobiluncus.

So once Gardnerella is established in a biofilm, it’s easier for these other bacteria to colonize, and since they are all living together in the same biofilm, they are all equally hard to get rid of. It’s a party, but not the kind we want to be invited to.

Can Gardnerella cause UTIs?

Not directly, but it can make it easier for E. coli to cause infections. E. coli is the most common cause of UTIs.

Like bacterial vaginosis, E. coli UTIs can come back again and again. There are a couple of reasons this can happen, but one thing E. coli can do is hang out inside bladder cells (these are called intracellular bacterial communities or IBCs). Hiding out in these cells protects E. coli from the immune system, allowing it to chill out until the time is right to re-infect the bladder.

Recent research has shown that if Gardnerella gets into the bladder, it can cause these E. coli IBCs to become active, essentially luring E. coli out of its hiding place.

The result is a UTI flare-up. So while Gardnerella alone does not cause UTIs, it can be the trigger for an episode.

What does it mean if you test positive for Gardnerella?

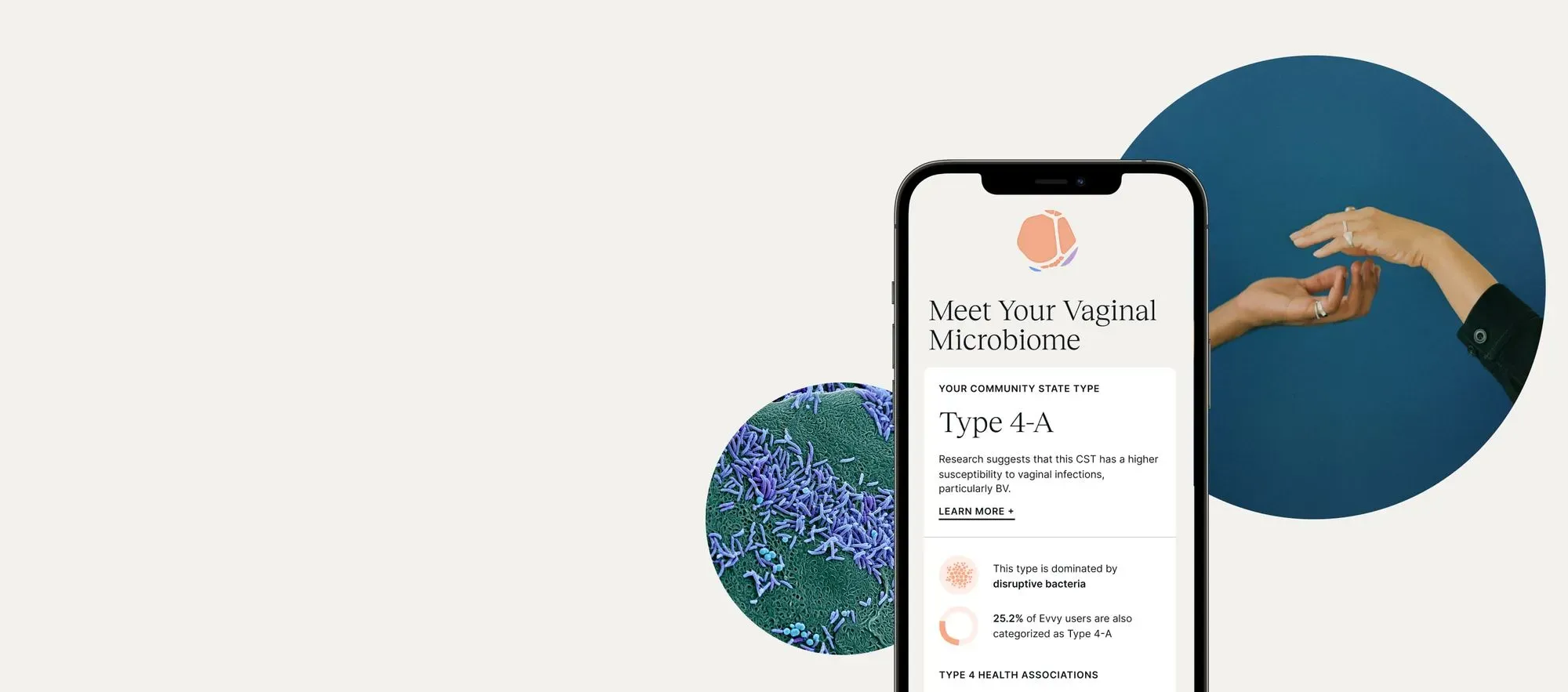

Everything treatment-related should be a direct conversation with a healthcare provider, such as your OB-GYN. Evvy tests for 700+ bacteria and fungi that can impact the vaginal microbiome, making it an incredibly powerful tool if you believe Gardnerella may be present down there.

Other than detecting Gardnerella, a provider will likely also want to discuss what other microbes are present and what your symptoms are to determine your best care options.

If you're eligible for Evvy Care and you have Gardnerella in your results, an Evvy-affiliated provider can provide you with a care plan especially targeted towards reducing Gardnerella and building back the more protective microbes.

Gardnerella treatment

According to clinical guidelines, the presence of Gardnerella alone doesn’t need to be treated in the absence of any vaginal symptoms or discomfort.

If you do have symptoms like abnormal vaginal discharge, discomfort, itching, or soreness, and Gardnerella is in your sample, it's important to bring up these details to a physician or in the health history form that comes with every Evvy test.

The presence of Gardnerella alone doesn't need treatment, but when it causes BV, it's important to see your healthcare provider. Aside from being uncomfortable, untreated BV can lead to an increased risk of:

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Fertility issues

- Adverse pregnancy outcomes (like preterm birth)

- STIs.

Remember how we said that taking an Evvy test can help further the research on whether or not Gardnerella acts in the vaginal microbiome depending on who its neighbors are? We hope that the metagenomic sequencing we use will help give us insights into Gardnerella and other microbes to provide you and other people with vaginas with the best, most personalized care pathways available.

FAQs

What does it mean if you test positive for Gardnerella?

It likely just means that you have Gardnerella in your vaginal microbiome, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Gardnerella can be a part of your healthy vaginal flora without causing issues or symptoms. The problems arise when Gardnerella bacteria overgrow and disrupt the natural balance of your vaginal microbiome.

What causes a Gardnerella infection?

Gardnerella vaginalis is a type of bacteria, rather than a condition in itself, so it doesn’t have a “cause”. When it overgrows, however, it can lead to bacterial vaginosis. Researchers aren’t sure what exactly causes Gardnerella vaginalis overgrowth in some people, but they have identified certain risk factors, including sexual intercourse (with multiple sexual partners or a new sex partner), hormonal fluctuations, your period, smoking cigarettes, chronic stress, and douching.

Is Gardnerella vaginalis an STD?

No, Gardnerella isn’t a sexually transmitted disease (STD) — and neither is bacterial vaginosis. That being said, sex can be a trigger for bacterial vaginosis. Research shows that having unprotected sex or sex with multiple people can increase your risk of developing bacterial vaginosis.

Is Gardnerella a UTI?

Gardnerella is a type of bacteria linked to bacterial vaginosis. That said, some research has found a link between Gardnerella and urinary tract infections, too. Although Gardnerella doesn’t directly cause a UTI, one study found that Gardnerella vaginalis can trigger E. coli (the bacteria responsible for UTIs) already hiding in the bladder to cause a UTI.

Can I give Gardnerella to my boyfriend?

Yes, you can spread the Gardnerella bacteria to your boyfriend during sex, but that doesn’t mean it will result in an infection. Men often carry BV-associated bacteria like Gardnerella on their penile microbiome (yep, penises have a microbiome too) and in their semen or urethra, but they can’t get BV. If your boyfriend is experiencing unusual symptoms like penile discharge, itching, or a burning sensation when he pees, it’s most likely caused by a different infection.